Prof. Valter Longo in his lab at University of Southern California. Photo courtesy of USC.

Sounds too good to be true, right? But a growing stockpile of data suggests that it is indeed possible.

New research into fasting, and specifically an approach called the Fasting Mimicking Diet (FMD), is shedding light on how to use foods and diet patterns to promote longevity and prevent or reverse degenerative diseases. It’s an approach that is catching on with functional medicine practitioners—and their patients. Some are seeing very meaningful results.

What is FMD?

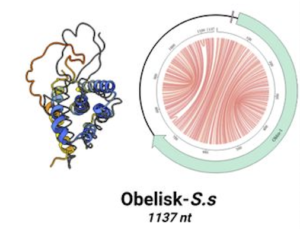

The FMD is a carefully calibrated regimen of high-fat, low protein, low-carb meals that periodically spur the body into fasting physiology—without a person needing to truly fast. It was developed by gerontologist Valter Longo, PhD, at the Longevity Institute at University of Southern California (USC). Longo is a professor of gerontology at USC and also director of the Program on Longevity and Cancer at IFOM (Molecular Oncology FIRC Institute) in Milan, Italy.

Simply put, when fuel and nutrients are limited, old cells are triggered into states of self-degradation and disassembly (autophagy). At the same time, stem cells go into regeneration mode. In essence, the body is trying to rid itself of the unnecessary, while strengthening the necessary vital tissues and functions.

In the context of a controlled caloric restriction such as fasting, the net result is regenerative and restorative. This is why people often feel quite healthy and invigorated after brief but intentional fasts. Prolonged caloric restriction, however, is obviously detrimental to health and wellbeing.

Researchers and clinicians have for decades sought ways to obtain the health benefits of fasting, without the actual fasts. This quest was the main motivator for Longo and his colleagues in developing the “Fast Mimicking Diet.”

Not to be confused with intermittent fasting, which does require someone to actually stop eating for specific time periods, Longo’s FMD system—known as ProLon (Promoting Longevity)—induces many of the same metabolic changes, but doesn’t require patients to skip meals. Rather, it obliges them to make intentional food choices for specific five-day periods over the course of a year.

Speaking at the 2019 Integrative Healthcare Symposium, Longo reviewed the science behind the FMD, with specific emphasis on the diet’s role in preventing and reversing cardiometabolic disease and cancer.

Molecular Foundations of Aging

Perhaps Dr. Longo was fated to become a longevity researcher. Born in Genoa, his ancestors are from Calabria—the “toe” of Italy’s boot, home to some of the longest-lived people in the world. But his first love was the guitar, and he had rock n’ roll aspirations before he was bit by the science bug.

A growing interest in biology—specifically the biology of aging—eventually drew Longo to the US. He studied biochemistry at University of North Texas and later went on to UCLA in 1992, where he joined the lab of Roy Walford—a colorful and controversial pioneer in the study of calorie restriction and health.

At that time, Longo says, UCLA was one of the premier destinations for longevity research.

His early work focused on the fundamental mechanisms of aging. Walford had already shown that periodic calorie restriction was strongly associated with longevity in mice; conversely, mortality correlated with continuous caloric excess. Other researchers had shown similar patterns across many different species.

Longo wanted to understand the biochemical mechanisms underlying this phenomenon.

“If aging is the central risk factor for all major diseases, Longo believes it is smarter to intervene on aging itself than to try to prevent and treat diseases one by one.” ––Prof. Valter Longo

After a few years studying rodents, he decided to take a few steps back on the evolutionary chain. He turned his focus to baker’s yeast, a single-cell organism that would allow him to study the molecular foundation for aging, life, and death.

He discovered that if he periodically starved the yeast and only gave them water, they lived twice as long as they did when “fed” regularly.

He also found that high sugar consumption is as big a problem for yeast as it is for humans. In fact, it’s directly responsible for yeast aging fast and dying early.

Sugar activates two genes––RAS and PKA––which are known to accelerate aging, Longo told IHS attendees. At the same time, sugar inactivates factors and enzymes that protect against oxidation and other types of damage.

For several years, this research was ignored and even dismissed, because most scientists believed Longo’s work on microorganisms had no relevance to humans.

He himself firmly believed that many, if not most, organisms—from the smallest to the biggest—age the same way, and that the genes and “molecular strategy” to achieve longer lifespans would be similar across species.

Getting these ideas published was no easy feat.

As he writes in his book, The Longevity Diet, “It would take six years for our data on genes activated by sugars to be published, along with the discovery of the pro-aging genes activated by amino acids and proteins. Eight more years passed before different laboratories would confirm these data experimentally in mice, and another ten years before my own lab provided initial evidence that similar genes and pathways may protect humans against age-related diseases.”

Little People, Big Discoveries

Alongside his lab work, Dr. Longo was also studying centenarians and supercentenarians (those who reach age 110 and beyond). He also conducted research examining a unique group of people living in Southern Ecuador with particular form of dwarfism called Laron syndrome, who lack the receptor for growth hormone (Rosenbloom, AL. et al. N Engl J Med. 1990; 323: 1367-1374). Prof. Longo in Ecuador with two people who have Laron syndrome. Photo courtesy of Discover magazine.

Characterized by extremely short stature, and prone to hypoglycemia and truncal obesity, people with Laron are notably “resistant” to diabetes and cancer, relative to non-Laron people of similar ethnicity and geography (Guevara-Aguirre, J. et al. Sci Trans Med. 2011; 3(70):70ra13). This congenital defect in growth hormone receptors also appears to confer an anti-aging effect (Bai, N. Sci Amer. “Defective Growth Gene in Rare Dwarfism Disorder Stunts Cancer and Diabetes.” Feb 2011).

After studying people with Laron for five years, Longo and his colleagues found a marked decrease in incidence of cancer and diabetes. This was despite high rates of smoking, alcohol consumption, poor diet, and a largely sedentary lifestyle.

The difference was especially apparent when Longo compared the individuals with Laron to non-Laron immediate relatives living in the same households and eating the same foods. Among those with the syndrome, the prevalence of cancer deaths was about 3%. Among their relatives, prevalence was around 22%.

Also, despite the fact that they were twice as likely as their non-Laron relatives to be obese, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes was nil in the Laron group but 7% among their relatives. The observations are attributed to the fact that people with Laron have an inordinately higher sensitivity to insulin.

Another striking finding was that those with Laron appeared to be generally far more youthful than their biological age. Their average cognitive function scores were typical of much younger individuals.

“Our findings made this group of short individuals from remote villages in Ecuador famous around the world,” Dr. Longo writes. “Everyone wanted to hear about this group of little people who appeared to hold the secret that could protect everyone from cancer, diabetes, and possibly other diseases.”

As for the centenarians he’s studied, their main diets shared some key commonalities. What they consume is mostly plant-based, with lots of nuts and fish, low in proteins, sugars, and saturated or trans fats, and high in complex carbohydrates from beans and other plant-based foods.

Additionally, they only ate two or three times a day, comsumed light meals in the evening, and typically finished eating before dark.

Juventology: The Study of Youthfulness

Essentially, the FMD makes use of physiological survival mechanisms that are deeply hardwired into our biology.

Dr. Longo believes that in order to optimize disease prevention and treatment, “We need to know what causes disease at the molecular and cellular level and to understand how we can return these molecules and cells to their youthful, fully functioning states. To attempt to treat a disease without this information is like trying to fix a car without knowing how its engine or electrical system works.”

He refers to his field as “juventology”––the study of youth––as opposed to gerontology, the study of aging and senescence.

Under his programmed longevity theory, he contends that how and why we age is not as interesting as how we stay young. Last year, in the journal Aging Cell, Longo stressed the concept of healthspan instead of lifespan. “We are so used to associating death with cancer, heart disease, or another illness that the concept of ‘dying healthy’ seems alien,” he said.

The identification of conserved genes and pathways that regulate not only lifespan, but also healthspan, has fostered greater understanding of the relationship between nutrients, signal transduction proteins, and aging.

It has also provided evidence for the existence of multiple “longevity programs” within cells, which are selected based on the availability of nutrients.

Periodic fasting and other dietary restrictions can promote physiological entry into a stress resistance state “characterized by the activation of cell protection, regeneration, and rejuvenation processes. Intermittent periods of reduced protein, amino acid and glucose availability lead to downregulation of growth hormone, IGF-1, mTor-S6K, and PKA signaling. These processes can also activate regenerative processes that lead to rejuvenation, which are independent of the aging rate preceding the restricted period,” Longo writes (Longo, VD. Aging Cell. 2018; (18)1: e12843).

If aging is the central risk factor for all major diseases, Longo believes it is smarter to intervene on aging itself than to try to prevent or treat diseases one by one.

“Even great success against one disease may be minimal or rendered irrelevant if accompanied by an increased incidence of another. Few people know…that curing cancer or cardiac disease today would only increase the average lifespan a little over three years,” he said.

The Science Behind FMD

Longo and a growing cadre of researchers and clinicians believe the FMD is the key to unlocking this longevity program. Numerous cell culture and animal studies have laid a solid foundation for substantiating that claim, and clinical trials to further explore it have started to emerge.

In a 2017 human study published in Science Translational Medicine, Dr. Longo and his team were able to show that being on a FMD diet once a month for three months reduced several markers of aging and disease.

For this study, they randomized 100 generally healthy participants into two groups and tested the effects of the FMD—five days per month for three months on a diet low in calories, sugars, and protein, but high in unsaturated fats—versus an unrestricted diet, on markers and risk factors associated with aging and age-related diseases.

After the initial three months, control diet subjects were switched over to the FMD program, resulting in a total of 71 subjects who completed three FMD cycles.

The FMD significantly reduced body weight, as well as abdominal and total body fat; lowered blood pressure; and decreased insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), with no serious adverse effects.

A post hoc analysis showed that the patients who had the highest baseline risk for cardiometabolic disease also had the greatest beneficial changes in BMI, blood pressure, fasting glucose, IGF-1, triglycerides, total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and C-reactive protein.

While on the FMD, subjects typically show a spike in stem cell activity, as well as a host of beneficial changes in lipid profiles: lower TGL, lower total cholesterol, lower IGF, loss of visceral adipose tissue, and lower c-reactive protein (Wei, M. et al. Sci Transl Med. 2017; 9(377): eaai8700).

There are currently 39 FMD clinical trials planned or underway—most at major universities, and entirely independent of Dr. Longo’s lab or the marketers of ProLon.

Real Food for Real Results

The ProLon diet program, developed and marketed by a company called L-Nutra, is an all-inclusive meal plan based on Longo’s research. L-Nutra’s meal packs are prepared from minimally processed whole foods and are entirely drug-free. They are also gluten- and dairy-free.

The five-day protocol delivers a total of 1,100 calories on the first day, and roughly 770 calories on each of the four subsequent days. Patients receive a box containing the five days’ worth of meals—including soups, snacks, beverages, meal bars, herbal teas, and dietary supplements.

ProLon is entirely plant-based and includes many highly nutritious foods like olives, kale, quinoa, and a host of vegetables. The entire five-day meal plan is built out of 66 ingredients, combined in recipes with a focus on appealing taste, rather than deprivation or self-punishment.

The most recent innovation to emerge out of Dr. Longo’s work is Chemolieve, a four-day FMD meal program designed specifically for cancer care.

FMD & Cancer Care

Standard cancer treatment protocols generally involve feeding patients heavily before they begin chemotherapy, providing extra nutrients to counteract the risk of cachexia and symptoms of weight and muscle loss.

According to Longo, that’s the wrong approach—especially if what patients are eating is high in protein and sugar. Heavy caloric loads, he contends, predispose patients to chemotherapy side-effects, metabolically pushing normal healthy cells into growth mode while the chemotherapy simultaneously delivers its cytotoxic effects.

Fasting, he says, has the opposite effect. It is highly protective and has potential to actually improve chemotherapy outcomes while reducing side effects.

Four days of fasting prior to chemotherapy slows the pro-growth mode in normal tissue, rendering it less susceptible to the cytotoxic effects of the chemo drugs. In addition to cutting the risk of adverse effects in normal tissue, fasting may also sensitize cancer cells to the drug treatment. Tumor tissue and normal tissue have differential stress resistance, Longo explained.

Brief caloric restriction also rejuvenates white blood cells, facilitating T-cell response to cancer tissue, which could potentially improve survival.

In mouse studies, caloric restriction prompts the same decrease in tumor volume as cisplatin therapy, and the combination of chemotherapy and fasting promotes cancer-free survival in mice, compared to chemotherapy alone.

Caloric restriction starves damaged or abnormal cells and forces them into autophagy. “FMD pushes the body to break components down and activate the stem cells,” Longo said. “Genes start turning on like they did when you were born. There are very coordinated rejuvenation programs embedded in our biology.”

But the reality is that most cancer patients are unable or unwilling to fast.

This is where a carefully tailored FMD can be very useful. It triggers the regenerative responses of fasting, without subjecting an already strained and possibly undernourished individual to the intense stress of a true fast.

There are five studies looking at the Chemolieve diet planned or already underway at USC, the Mayo Clinic, Leiden University, and the University of Genoa.

FMD’s Future

Longo played a role in the commercial development of ProLon and Chemolieve, but he does not personally derive financial gain from the products or from L-Nutra. Money from the product sales goes directly to his Valter Longo Foundation, to support “research aimed at rapidly developing inexpensive, creative, integrative therapies for the treatment of serious diseases, and the identification of strategies to prevent illness and promote longer, healthier lives.”

“The more the company grows, the more the foundation grows, and the more research we can do,” he said. “In a couple of years, we could have billions of dollars and another level of grant programs.”

He also emphasizes that FMD is not a fad diet, nor is it based on toxic ingredients or physiological tricks. At its root, it is really about the intelligent use of food.

“Food is arguably the most powerful drug out there, with the power to reduce cancer and cardiovascular disease by half. It’s crazy that NIH invests such a miniscule amount of money in food vs. pharma.”

Though research is still in its early stages, Longo and other advocates of the FMD believe it could play a beneficial role in preventing or managing conditions like diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and various forms of dementia.

END