For the first time in over two decades, the Food and Drug Administration is mandating changes to the way foods and dietary supplements are labeled. The new regulations call for significant revision of numerous long-used health and nutrition standards, and will affect healthcare practitioners, patients, and industry players alike.

For the first time in over two decades, the Food and Drug Administration is mandating changes to the way foods and dietary supplements are labeled. The new regulations call for significant revision of numerous long-used health and nutrition standards, and will affect healthcare practitioners, patients, and industry players alike.

In May of 2016, the FDA published two final rules, the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Label Final Rule and the Serving Size Final Rule, in the Federal Register. The proposed rules either modify or add to numerous existing FDA mandates surrounding food and supplement packaging. The new rules constitute a major overhaul of labeling language, and they were originally slated to take effect as early as July 2018. But the FDA recently pushed back compliance dates by two years to allow manufacturers additional time to prepare.

The upcoming rule changes “reflect updated scientific information, including the link between diet and chronic diseases such as obesity and heart disease,” explained Deborah Kotz, Press Officer for the FDA’s Office of Media Affairs. “The new labels will make it easier for consumers to make better informed food choices,” she added.

All foods and multivitamins, single letter vitamins, and minerals carrying nutrition facts or supplement labels will be affected by the changes, many of which will be relevant for any practitioners who recommend supplements or nutrition-based interventions.

The updates center on two key areas: adjustments to current daily value recommendations, and new units of measure for several essential nutrients.

Servings Resized

“Today, people are eating differently, so some of the serving sizes on labels — and the amount of calories and nutrients that go with them — are out of date,” Kotz told Holistic Primary Care.

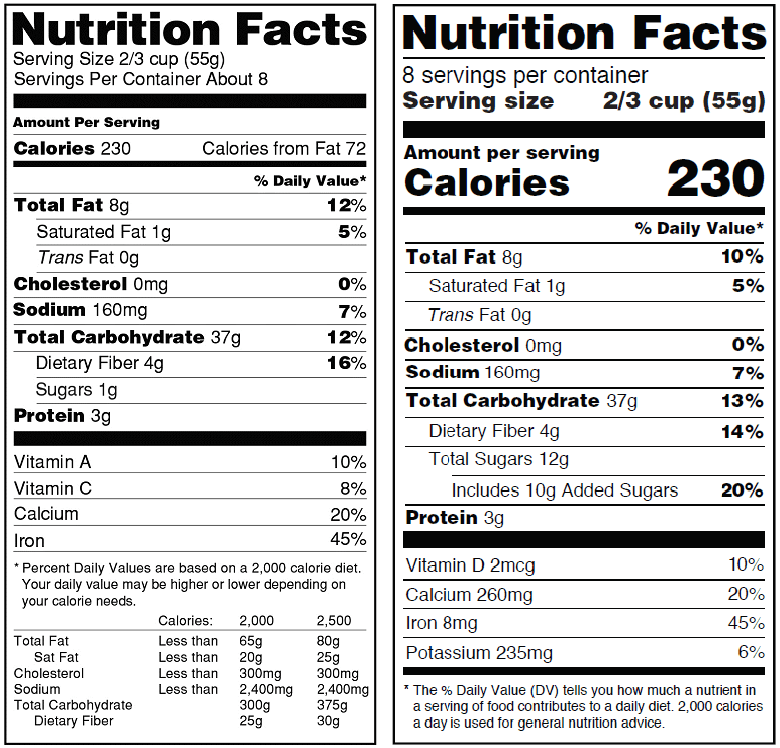

For one thing, the FDA is mandating a redesign of its iconic “Nutrition Facts” panel so it will highlight items like “servings” and “calories,” printed in a larger bolded font for greater emphasize on the calories per serving.

Many foods will receive updated serving sizes to more accurately represent current American eating and drinking habits. The FDA notes that “by law, serving sizes must be based on amounts of foods and beverages that people are actually eating, not what they should be eating.” Consumption patterns have shifted over time towards ever larger portions, yet serving size quantification on product labels have not changed since their initial introduction in 1993.

To give one example, under the new rules, a serving of ice cream will increase to 2/3 cup, up from the former 1/2 cup. Similarly, the serving size for soda will jump from 8 ounces to 12 ounces. That means Americans will get a much more realistic–and hopefully sobering–picture of their total calorie consumption. This could, at least in theory, support healthier food choices.

New Daily Values

The FDA is also establishing new or revised daily values (DVs) for a number of important nutrients. Many of the old DVs are based on decades-old science, some of which goes back as early as 1968. For the update, the agency is drawing upon current nutrition science data from sources like the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM; formerly the Institute of Medicine) and the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion’s 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA).

Most vitamins and minerals will receive adjusted DVs.

For example, the new upper limit for sodium will drop from a recommended 2,400 mg to 2300 mg per day, aligning with both the 2005 and 2010 DGA recommendations as well as a 2013 IOM report on sodium intake in the general population.

Also following the IOM’s stance on potassium as a beneficial blood pressure-lowering nutrient, FDA is raising the recommended daily intake of potassium from 3,500 mg to 4,700 mg per day.

Calcium recommendations will also increase notably from 1,000 mg to 1,300 mg daily. Choline, for which there previously was no recommended daily intake, now has a DV of 550 mg.

Spotlight on Added Sugar

The recommended daily intake (RDI) values for several macronutrients will change as well. The DV for total carbohydrates is being cut from 300g to 275g, and nutrition facts panels will more clearly delineate different forms of carbs.

In an effort distinguish intrinsic sugar content from sugars added during the manufacturing process, food and supplement companies must now indicate specifically how much added sugar a product contains. This new rule applies not only to conventional food products, but to nutritional supplements as well.

In an effort distinguish intrinsic sugar content from sugars added during the manufacturing process, food and supplement companies must now indicate specifically how much added sugar a product contains. This new rule applies not only to conventional food products, but to nutritional supplements as well.

In addition to inserting a new mandatory “added sugars” line — which manufacturers previously weren’t required to label — FDA also established a new 50 g per day DV for added sugars. The former “Sugars” line will change to “Total sugars,” with the phrase “Includes ‘X’ g Added Sugars” indented and declared directly below the “Total sugars” line on the label.

“Our goal is to increase consumer understanding of the quantity of added sugars in foods,” Kotz stated.

In typically bureaucratic double-speak, she cautioned that excessive consumption of added sugars can make it, “more difficult to also eat foods with enough dietary fiber and essential vitamins and minerals and still stay within calorie limits.”

The sugar labeling guidelines are in alignment with the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Committee Report that supports reducing calories from added sugar in the diet to less than 10 percent of all calories consumed. They also reflect the strong and consistent evidence showing an association between high sugar intake and risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk.

On the old nutrition facts label, it was never clear how much added sugar a product contained — but with this information now more clearly defined, people can conceivably choose whether or not to reduce their consumption of products containing additional sugars.

In theory, labeling added sugars on dietary supplements makes it easier for people to quickly identify how their supplements factor into their daily sugar consumption. “If a dietary supplement provides 10-20% of the recommended daily intake for added sugar, then the consumer may decide they want to save this for a cookie or something more fun to eat,” said Duffy MacKay, Senior Vice President of Scientific and Regulatory Affairs at the Council for Responsible Nutrition (CRN).

CRN was one of a number of nutrition industry organizations that provided extensive comments to FDA as the final labeling rules were being drafted.

MacKay believes the new sugar rules will have significant impact on supplement and food companies. “For industry, the added sugar regulations will likely cause significant formulation changes,” MacKay expects. “There are gummy supplements, chewable vitamins, and flavored drink mixes that contain sugar,” he explained.

In some cases, that sugar is derived from naturally occurring sources. For instance, natural fruit juice in and of itself is not considered an “added sugar,” but if fruit juice is added to another product in order to sweeten it, then suddenly that natural sugar becomes an “added” one. Determining the exact amount of intrinsic versus added sugars in a product can be difficult, and limited testing methods exist for manufacturers required to make that distinction.

Fiber Wars

Rules and recommendations around fiber will undergo major changes.

In addition to raising the daily value for fiber from 25g to 28g, the FDA also established a new definition for dietary fiber. Now, only certain isolated or synthetic non-digestible carbohydrates pre-determined by the FDA to confer specific beneficial physiological effects can be referred to as “dietary fibers.” Those benefits include attenuation of blood glucose, reduced energy intake, improved laxation, and lower cholesterol.

For manufacturers, compliance with these new dietary fiber regulations presents one of the biggest hurdles.

The FDA’s current short list of approved fibers includes only beta glucan, psyllium husk, cellulose, guar gum, pectin, locust bean gum, and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC).

This leaves out some of the common forms of fiber such as inulin and others, that manufacturers currently use widely. The updated fiber definition not only affects the claims that producers can make about fiber, it also presents challenges for manufacturers attempting to accurately calculate a product’s fiber content.

MacKay explained that in order to add a new item to the FDA’s list of accepted fibers, manufacturers must file a petition containing scientific data that demonstrates the fiber’s health benefits.

“This is the first time the FDA has required a nutrient to meet a physiological-based definition, since all other nutrients are defined by structure,” he noted.

Needless to say, these new regs will significantly impact various nutritional products and their fiber content claims. A number of companies have filed petitions with the FDA to reconsider the new fiber rules. The FDA has not yet responded to any of them.

“If the FDA does not respond to filed petitions before the compliance date, then products that include non-approved fiber ingredients would be required to be relabeled to reflect the loss of fiber from that ingredient,” he said. “However, the FDA could respond later and the company would again have to change labels.”

It is important to understand that for manufacturers, label changes are expensive, resource intensive, and burdensome — especially when they must be done twice. The “regulatory uncertainty around expensive business decisions is making it difficult for companies to plan,” MacKay said.

Fats: Focus on Type

Fats will see changes under the new provisions as well, with the recommended daily value for fat bumping up from 65g to 78g. The FDA will continue to require the labeling of “Total Fat,” “Saturated Fat,” and “Trans Fat,” but the “Calories from Fat” item will be removed. Why?

FDA made the decision based on research showing that from a health impact perspective, the type of fat is more important than the total fat calories a product contains.

Notably, while the FDA’s current nutrition facts panel has remained virtually unchanged for more than 20 years, the one exception was the addition of trans fat to food labels in 2006. In 2015, the administration published a final determination that partially hydrogenated oils — a major source of artificial trans fats– are not “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS), though manufacturers can currently use some partially hydrogenated oils approved as food additives and can petition FDA for the use of others.

Moving forward, the rules prohibit manufacturers from using partially hydrogenated oils for any purpose other than those already authorized by FDA.

Kiss the IU Goodbye!

The new labeling provisions will change the units of measure used to quantify a number of important vitamins.

Arguably, the biggest change is that FDA is completely eliminating the International Unit (IU) as an accepted unit of measure. For vitamins A, D, and E, IUs will be replaced with metric units–micrograms (mcgs) or milligrams–per the recent Institute of Medicine recommendations for nutrition labeling.

The venerable IU system was established decades ago, in an effort to try to quantify substances based on their biological activity rather than simply their weight or volume. It has been applied largely to fat-soluble vitamins, some hormones, and some drugs. The weight or volume of an IU of a particular substance is dependent on its biological activity as defined in a set of standards established by the World Health Organization’s Expert Committee on Biological Standardization.

It was an innovative idea at the time it was developed, but most nutrition experts today believe the IU system is full of arbitrary values and has largely been outmoded.

The omission of IUs from supplement labels will undoubtedly cause confusion for many practitioners and consumers who’ve become accustomed to the IU system–even if they never really knew what the unit actually meant. The change will require a bit of re-education. For instance, clinicians accustomed to recommending say, 400 IU of vitamin D, will now need to know that this equals 20 mcg.

Because Vitamin D is so widely expressed in IUs, however, manufacturers can voluntarily continue to use the old fashioned units — in addition to the required mcgs — on their labels. “Since the FDA determined that vitamin D is a nutrient of public health significance, we consider that voluntary labeling in IUs for vitamin D will assist consumers in maintaining healthy dietary practices,” Kotz said.

Folic Acid: Expect Confusion

The approved unit of measure for folate will also change—and that change could cause a lot of confusion.

Instead of micrograms, folate will now be expressed in mcg Dietary Folate Equivalents (DFE). The Food and Nutrition Board at the IOM developed the DFE system to reflect the higher bioavailability of isolated folic acid as compared to food-based folate.

The new RDI will be expressed as 400 mcg DFE, which is equivalent to 240 mcg of folic acid in the old labeling system. For pregnant women wishing to reduce the risk of neural tube defects (NTDs), the new DV is 600 mcg DFE (about 360 mcg under the old labeling guidelines). That’s on top of whatever folate they may get from food sources.

But those numbers are out of step with the most recent 2017 guidelines from the US Preventive Services Task Force, which recommend that reproductive-age and pregnant women take at least 400-800 actual micrograms of supplemental folic acid—a guideline based on solid clinical trials.

In other words, the FDA’s new folate DV for pregnant women (600 mcg DFE, which delivers 360 actual micrograms) falls short of the most current evidence-based recommendations.

It’s a problem of which the FDA is aware. “Various government and public health organizations recommend that women of childbearing age consume 400 mcg folic acid/day to prevent neural tube defects,” CRN’s Dr. MacKay told Holistic Primary Care. “Consuming the RDI of 400 mcg DFE does not achieve what is recommended for NTD prevention, and this is likely to confuse consumers and healthcare practitioners.”

MacKay says the misalignment between the new labeling rules and the best public health recommendations is “an unfortunate and unintended consequence of changing the units of measure for folic acid.”

He added that CRN voiced concerns to the FDA, which responded with a compromise allowing supplement makers to utilize the old-school microgram measurements in parentheses in addition to the new DFE designation when labeling their folate products.

“Bottom line is that women capable of becoming pregnant will need to be looking for products with 667-1,334 DFE to get 400-800 mcg of folic acid.”

Prepare for Patient Questions

Once these labeling changes become law–and currently it is unclear when, exactly, full implementation will be required– very few food or supplement products will remain untouched. Looking ahead, health practitioners need to educate themselves about the new terminology and the new units of measure. No doubt, patients will be coming in with questions.

Although single-ingredient botanical products may not be affected, most products that contain vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, amino acids and fibers–will be undergoing some label alterations under the new rules. Something as mundane as a basic multi-vitamin product will be subject to dozens of changes.

“The new regulation is massive,” MacKay explained, describing the 260 pages of complex FDA labeling requirements and guidance documents that manufacturers must confront.

Compliance will be especially challenging for smaller companies that may not have full-time, on-site regulatory compliance officers. “All companies, big or small, are required to read and understand the 260 page document,” says MacKay. They then must determine what changes they must make to remain compliant with new regulations.

Many of the proposed changes necessitate business decisions that impact companies across multiple departments. Under previous regulations, for instance, a product containing 1,000 mg of calcium could be labeled as providing 100% DV for calcium. But with the new DV of 1,300 mg, the same product will now provide just 77% DV. The supplement maker will have to determine whether to simply change the product’s label to reflect the new lower % DV, or to reformulate the product altogether, adding 300 additional mg of calcium to provide 100% DV.

Manufacturers will be making similar decisions for each nutrient with an updated DV. Formulation changes are complex and require many consideration. Companies will also need to reevaluate any label claims they make on their products, as newly defined criteria now restrict the use of terms like “high,” “rich,” and “excellent source of.”

Clinicians who use supplements should expect to see formulation changes for some–if not many–of the products they’re now recommending. This is not necessarily bad, but it is something that will require some measure of attention.

Originally, the FDA final rules listed a compliance deadline of July 26, 2018 for manufacturers with $10 million or more in annual sales, and July 2019 for manufacturers with less than $10 million in annual revenue. But last September, largely because so many manufacturers requested additional time to prepare, the FDA announced extended guidelines. Manufacturers now have until Jan. 1, 2020 and Jan. 1, 2021, respectively, to comply.

END