Hope is like a salve for the soul during times of great distress. But when it’s dispensed in the form of medical misinformation, hope can have dangerous––even deadly––consequences.

Hope is like a salve for the soul during times of great distress. But when it’s dispensed in the form of medical misinformation, hope can have dangerous––even deadly––consequences.

Earlier this Spring, President Trump lauded the “very encouraging” possibility that a pair of existing FDA-approved drugs––hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin––showed “tremendous promise” as potential treatments for COVID-19. He expressed a “good feeling” about the medications in widely-publicized press briefings and social media postings.

According to Trump, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) could prove to be one of the “biggest game changers in the history of medicine” and should be put to use “immediately” in the fight against the novel coronavirus. Medical experts, however––including top officials at the FDA and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)––were quick to temper the President’s enthusiasm towards the untested therapy.

Untempered Optimism

Longtime NIAID Director Anthony Fauci, MD, similarly cautioned Americans that the evidence that hydroxychloroquine might be an effective therapy for the coronavirus is, at this point, purely anecdotal or extrapolated from in vitro studies. FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, urged the public not to take “any form of chloroquine”––hydroxychloroquine’s older chemical cousin––unless prescribed by a health care practitioner.

Researchers are racing to study the clinical potential of chloroquine, as well as a host of other drugs, as treatments for COVID patients. Efforts underway today include trials of antibiotics, antivirals, and antiretrovirals like lopinavir and ritonavir (Kaletra), a drug combo typically used to treat HIV.

On April 5, Vice President Mike Pence announced the start of a large-scale trial to test the prophylactic efficacy of HCQ in front-line healthcare workers in the Henry Ford Hospital System in Detroit. Leaders of the trial, known as WHIP COVID-19, hope to enroll 3,000 medical personnel. Participation is voluntary, and participants will be randomized to once-weekly HCQ, once daily HCQ, or placebo for eight weeks. FDA is providing the supply of HCQ to the Henry Ford System.

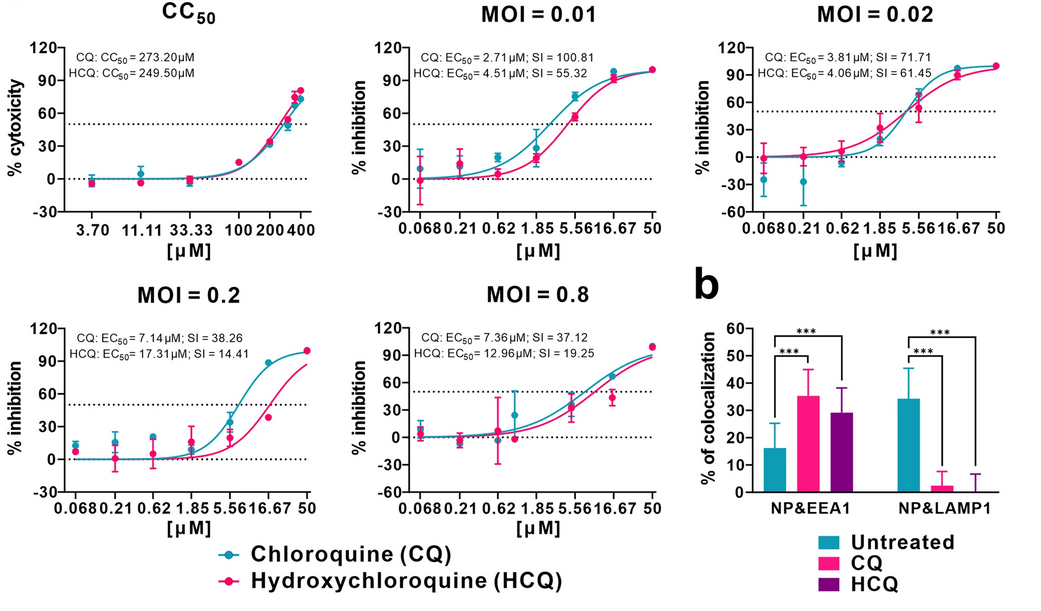

But to date, there is no solid evidence that CQ or HCQ are preventive or therapeutic. There are no other drugs with proven efficacy against COVID-19, nor is there a vaccine to prevent it. In a recent statement addressing the agency’s own research, NIAID describes numerous therapies under investigation––but notably, that list does not include chloroquine.

Evidence Gap

The study that Trump cited in support of his “good feelings” is questionable. The paper appeared online earlier this month in the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents and was co-authored by controversial French virologist Didier Raoult. Raoult has an unfortunate history of falsifying published data, and in 2006 he was banned from publishing his work in any of the American Society for Microbiology journals for a year.

His group’s recent, and arguably rushed, investigation of chloroquine was done in less than two weeks. Only 20 hydroxychloroquine-treated patients completed the non-randomized study, and six dropped out during follow-up due to early cessation of treatment. Of the six who left, three were transferred to an ICU, one died, and another stopped treatment because of the medication’s harsh side effects.

Concerns about limited evidence, however, haven’t stopped the federal government from pushing to make chloroquine more available to practitioners treating coronavirus patients.

In late March, the FDA issued an “emergency use authorization” (EUA) for both chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. The EUA does not mean that FDA has formally approved HCQ or CQ as COVID-19 treatments; rather, it frees up caches of the drugs from the government’s Strategic National Stockpile for emergency use during the coronavirus outbreak.

The evidence that FDA requires in order to green light to a new drug–or a new indication for an old one–may very well emerge from the trials now underway. But data won’t be available for weeks at earliest, more likely months.

Research over the last several decades shows that in addition to its potent anti-parasitic properties, chloroquine also has anti-inflammatory effects. There is also evidence from animal studies that chloroquine inhibits the systemic release of inflammatory cytokines like TNF and HMGB1. This cytokine-quelling effect, along with evidence from the SARS epidemic indicating that chloroquine has antiviral properties, is what led physicians in China to try the drug in COVID patients.

Until there is a solid body of evidence, the Centers for Disease Control is trying to temper undue enthusiasm about CQ and HCQ, and to dissuade practitioners from widely prescribing the drugs.

On April 8, the CDC removed its previously posted CQ and HCQ prescription and dosing guidelines from its COVID webpages. The updated page says simply that CQ and HCQ are “under investigation in clinical trials for pre-exposure or post-exposure prophylaxis of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and treatment of patients with mild, moderate, and severe COVID-19”

Irrational Action

The absence of trustworthy research has not deterred some Americans from running with the President’s under-educated optimism.

Within days of Trump’s enthusiastic tweets, reports spread of a Phoenix-area man who died, and whose wife was hospitalized, after self-medicating with a fish tank cleaning product containing chloroquine phosphate. The compound is an ingredient in many commercial aquarium cleaners, and shares a name with the related anti-parasitic drug chloroquine. But is not formulated for human use.

The Arizona couple, both in their 60s, reportedly viewed televised briefings during which the President discussed chloroquine’s possible benefits. They realized they had a chloroquine-containing product used to treat their koi fish. Afraid of falling ill from COVID, they decided to mix some of the aquarium cleaner with soda and ingest it as protection. Twenty minutes later they called 911, reporting severe symptoms including vomiting, dizziness, and respiratory distress.

News of the couple’s accidental self-poisoning prompted swift responses from medical professionals warning about the danger of taking untested drugs.

Steven Solomon, DVM, Director of FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine, issued a letter urging that “People should not take any form of chloroquine unless it has been prescribed by a licensed healthcare provider and is obtained through a legitimate source.” He clarified that products sold for aquarium use “have not been evaluated by the FDA to determine whether they are safe, effective, properly manufactured, and adequately labeled for use in fish––let alone humans.”

In a statement from Banner Health, which operates the hospital into which the Phoenix couple was admitted, Daniel Brooks, MD, wrote in no uncertain terms that, “We are strongly urging the medical community to not prescribe this medication to any non-hospitalized patients.”

Not Just a Malaria Drug

How exactly did an old malaria drug become the Great Hope in the unfolding COVID crisis?

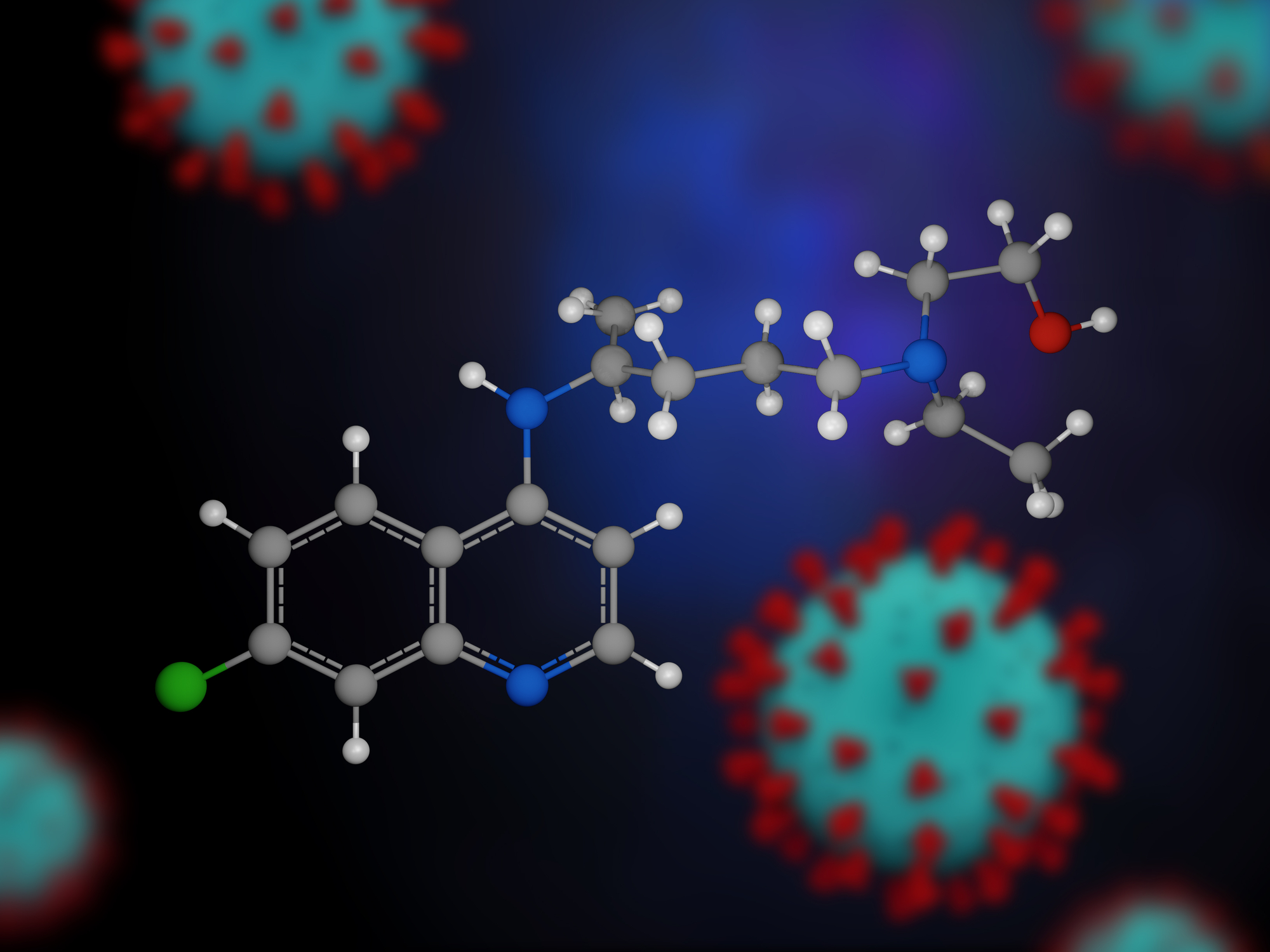

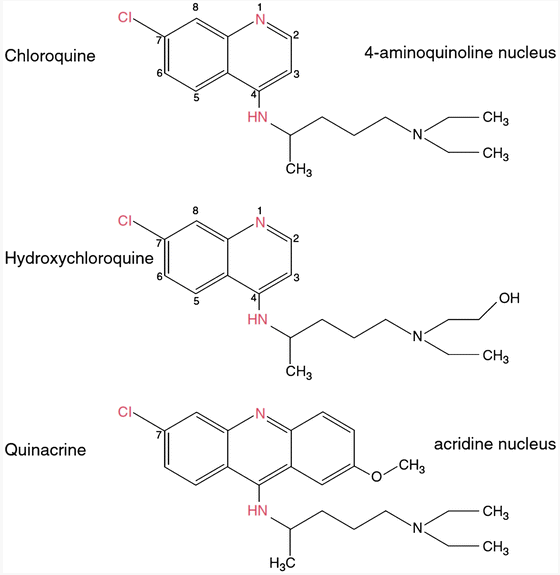

HCQ is a less toxic, hydroxylated version of chloroquine (CQ), a compound first synthesized in Germany by Bayer in 1934 and approved by the FDA in  1949. Chloroquine is a synthetic form of quinine, a naturally-occuring phytochemical found in the bark of cinchona trees native to South America. Quinine has a long history of traditional medical use, largely as a treatment for malaria (Achan, J et al. Malar J. 2011; 10: 144).

1949. Chloroquine is a synthetic form of quinine, a naturally-occuring phytochemical found in the bark of cinchona trees native to South America. Quinine has a long history of traditional medical use, largely as a treatment for malaria (Achan, J et al. Malar J. 2011; 10: 144).

For many years, chloroquine served the same primary purpose––and most current media reports portray it simply as a “malaria drug.”

But today, physicians commonly prescribe chloroquine for other conditions besides malaria. This is particularly true in industrialized nations, where prevalence of malaria is low.

Research over the last several decades shows that in addition to its potent anti-parasitic properties, chloroquine also has anti-inflammatory effects. Because it can help control inflammation, it is often prescribed for patients with autoimmune conditions. CQ and HCQ are standard components of care for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and multiple sclerosis.

There is also evidence from animal studies that chloroquine inhibits the systemic release of inflammatory cytokines like TNF and HMGB1, which, researchers argue, could slow the overwhelming and potentially fatal immune response that occurs in sepsis patients (Yang, M et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013; 86(3): 410–418).

This cytokine-quelling effect, along with evidence from the SARS epidemic indicating that chloroquine has antiviral properties, is what led physicians in China to try the drug in COVID patients.

Back in 2006, a group of researchers found that three compounds closely mimicking HCQ exerted antiviral effects in vitro against SARS-CoV, the 2003 coronavirus that killed thousands of people worldwide. “These new drugs may offer an interesting alternative for Asia, where SARS originated and malaria has remained endemic,” they concluded (Biot, C et al. J Med Chem. 2006; 49(9): 2845-2849).

Today, chloroquine research is exploding worldwide. Several clinical trials investigating HCQ to treat COVID-19 had been registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry by late February 2020 (Liu, J et al. Cell Disc. 2020; 6: 16).

A deluge of hot-off-the-press papers and editorials––mostly documenting case reports and small studies that haven’t been peer reviewed––appear almost daily in medical journals and newspapers.

One research group reported last month that a two-drug combo, chloroquine and remdesivir––an antiviral originally developed to treat Ebola––efficiently inhibited SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro (Wang, M et al. Cell Res. 2020; 30: 269–271). A few weeks later, a case report published in the New England Journal of Medicine described the use of remdesivir in treating the first patient infected by SARS-CoV-2 in the US. The authors note that they based their decision to administer remdesivir for compassionate use as the patient’s clinical status worsened (Holshue, M et al. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382: 929-936).

But not all the new studies are so hopeful. Jean-Michel Molina and colleagues at the Saint Louis Hospital, Paris, treated 11 confirmed COVID patients, eight of whom had high-risk preexisting conditions, with hydroxychloroquine 600 mg/d for 10 days plus azithromycin (500 mg on dy 1 and 250 mg on days 2-5).

Of the 11, one patient died, two were transferred to the ICU, and one had to discontinue treatment due to cardiovascular adverse effects.

There was no evidence that the chloroquine-azithromycin had any substantial antiviral effect. Nasopharyngeal swab samples taken on day six of treatment showed that 8 of the 10 evaluable patients were still positive for SARS-CoV2 RNA (Molina JM, et al. Medecine et Maladies Infectieuses. Mar 28, 2020)

Molina and colleagues say their findings “cast doubts about the strong antiviral efficacy of this combination,” and contradict an earlier French study by Gautret et al, showing reduced viral loads in a non-randomized, open-label study involivng 22 COVID patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin (Gautret P, et al. Int J Antimicrob Agents. Mar 20, 2020).

All of the published studies on chloroquine and COVID are preliminary open-label field trials with small patient populations. Clearly, large randomized controlled studies looking at this and other drugs, are urgently needed. Several are in the works.

In regions that rely on chloroquine to treat malaria, health officials have warned of a jump in overdose rates following Trump’s public endorsement of the drug for COVID. Nigerian health officials announced several cases of chloroquine poisoning and urged citizens against consuming large quantities of the medication to protect themselves from the coronavirus.

Gilead Sciences, maker of remdesivir, announced the initiation of two Phase 3 clinical studies to evaluate the safety and efficacy of remdesivir in adults diagnosed with COVID-19. The randomized, open-label, multicenter studies will enroll approximately 1,000 patients primarily at medical centers in Asia, although other countries with high numbers of diagnosed cases will also participate.

The World Health Organization has also launched a large multinational study, dubbed the Solidarity Trial, examining four potential coronavirus therapies: remdesivir; chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine; lopinavir and ritonavir; and the lopinavir-ritonavir combo plus the cytokine interferon-beta. WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said that his organization’s historic trial, which is slated to involve at least 45 countries and recently began enrollment, will “dramatically cut the time needed to generate robust evidence about what drugs work.”

In emergency scenarios like a pandemic, existing drugs with known safety profiles hold great appeal. The track for testing them is certainly faster than the long process of developing and testing novel compounds.

But crises like COVID also stoke tremendous public fear and pressure for action. Frightened people–and their political leaders–are not inclined to wait patiently for the scientific method to run its course.

Unfillable Refills

In the rush to “do something,” many people are making rash decisions with far-reaching consequences.

In regions that rely on chloroquine to treat malaria, health officials have warned of a jump in overdose rates following Trump’s public endorsement of the drug for COVID. Nigerian health officials announced several cases of chloroquine poisoning and urged citizens against consuming large quantities of the medication to protect themselves from the coronavirus.

Inappropriate anti-malarial consumption could heighten the growing global challenge of chloroquine resistance. The evolution of drug-resistant malaria parasites already poses a significant threat to disease control efforts in many parts of the world where chloroquine has been heavily used for decades.

In the US, the chloroquine hype is also impacting many patients who depend on the drug to manage autoimmune symptoms.

American pharmacists warn that legitimate chloroquine prescriptions are harder to fill. Some patients have been left scrambling to find desperately needed refills for a drug they’ve been taking for years.

Kaiser says, it is “actively converting patients from Plaquenil to other medications,” though it does not specify what those medications are. According to the Lupus Foundation of America, there are no alternatives to Plaquenil or related drugs for many people with lupus.

One SLE patient, a woman in her 40s with a long-standing HCQ (Plaquenil) prescription, reported in late March that her physician’s office abruptly stopped her usual refills without warning. She told reporters that she received a note from Oakland, CA-based Kaiser Permanente informing her that the coronavirus pandemic had caused a “worldwide shortage” of Plaquenil.

“We are therefore conserving the current supply for those who are critically ill with COVID-19,” the message from Kaiser stated. “Please do not contact your physician about an exception process to get a refill, as prescriptions will not be filled even if written by your physician.”

The note concluded with, “Thank you for the sacrifice you will be making for the sake of those that are critically ill; your sacrifice may actually save lives. We all hope this will be a short-term situation.”

The patient, who revealed only her first name, Dale, said she called several local pharmacies in search of a refill, but each one was “completely out of hydroxychloroquine.”

“I am already immunocompromised, and not taking this medication will likely put me into a lupus flare, making serious complications from COVID more likely,” she reported.

“The fact that [Kaiser] thanked me for my ‘sacrifice’ is disturbing,” she added. “I never agreed to sacrifice my health and possibly my life and cannot believe that I am being forced to do so.”

Similar anecdotes are popping up on social media platforms. Twitter user Anna Valdez, PhD, RN (@drannamvaldez) penned a compelling request on behalf of autoimmune patients like herself. “Please do not misuse hydroxychloroquine. This med is critical for people who have SLE, like me. I was told today that my prescription cannot be filled because the suppliers are completely out. Now I do not have the meds I actually need for an incurable disease I actually have.”

A message on Kaiser’s website claims that the managed care consortium is “taking steps to ensure we have adequate supply to meet the existing needs of patients who are taking these medications [hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) and chloroquine prescriptions], and also ensure access for severely sick patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infections.”

“Over the past few weeks, these drugs were identified as having a potential beneficial impact in the treatment of some severely sick COVID-19 patients who are hospitalized, which in turn has caused demand to rise dramatically. Supplies from drug manufacturers have not yet caught up.”

Kaiser says, it is “actively converting patients from Plaquenil to other medications,” though it does not specify what those medications are.

According to the Lupus Foundation of America, there are no alternatives to Plaquenil or related drugs for many people with lupus.

“For them, hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine are the only methods of preventing inflammation and disease activity that can lead to pain, disability, organ damage, and other serious illness,” the Foundation wrote in a statement. “An increase in lupus-related disease activity not only significantly impairs the health and quality of life of people with lupus but will also place further strain on health care providers and systems in a time of crisis.”

“Unfortunately, there are already verified reports across the country of pharmacies having major shortages of these vital drugs,” the statement continues.

While the Foundation applauds the pharmaceutical companies that have pledged to bolster their chloroquine supplies, it also urges that “increased production must not solely be done for the purpose of responding to COVID-19, but also to meet the existing needs of people with lupus.”

Drug Hoarding

Throughout the country, pharmacists are also sounding alarms about doctors who’ve called in questionable hydroxychloroquine prescriptions for personal, family, and prophylactic use. Patients who take the drug regularly say its cost has increased dramatically in recent weeks.

In response to the sharp upswing in HCQ prescriptions and prices, several state pharmacy boards have issued warnings to their constituents about appropriate prescribing.

The North Carolina Board of Pharmacy released a statement on March 23 describing “numerous reports from pharmacists across the state concerning new prescriptions for hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, azithromycin, Kaletra, and potentially other medications – often in large quantities with a high number of refills – to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic.”

The Board says it fielded claims ranging from prescribers writing prescriptions for themselves and family members, as well as for patients not yet exposed to or infected by the coronavirus.

“Board staff and public health officials are aware that some prescription drug wholesalers are reporting shortages of these drugs,” the organization stated. It also noted that “at least three other state boards of pharmacies have passed emergency rules limiting the circumstances under which these drugs may be dispensed, and their quantities.”

Chloroquine hoarding raises some major ethical questions about medication stockpiling in general.

How much data should medical professionals require before prescribing drugs for unstudied, off-label use? Who should have priority for access to medicines that are suddenly repurposed to meet new needs?

Holding Out Hope

Several major pharmaceutical companies have intensified the halo of hope surrounding chloroquine by donated stockpiles of the drug for use in coronavirus research and treatment. Mylan, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Novartis and Bayer are among the companies who’ve announced donations totalling millions of chloroquine tablets to hospitals and researchers studying COVID-19.

There are good reasons to believe that chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine could be helpful to some patients with COVID, but without data from larger and longer controlled studies, we do not know how effective these drugs will be or which patients are most likely to respond. Given the absence of good treatment options, it is well worth considering. But it is far too soon to make definitive recommendations for wide use.

While some people are putting big bets on chloroquine, others are pinning their hopes on the eventual production of a COVID vaccine. But as WHO’s Dr. Ghebreyesus told the world a few days ago, vaccines are “still at least 12 to 18 months away.” Even assuming the best possible outcome, vaccinations won’t necessarily prevent infection in all patients; as with the flu shot, some individuals who get vaccinated could still get sick.

In the meantime, Ghebreyesus pointed out that, “One of the most important areas of international cooperation is research and development.” His words are an important reminder that good scientific research requires time, patience, and collaboration.

END